Introduction

Let’s consider a relatively full-featured, practical use case for

reclanc. In this vignette, we’ll go over the basics of

fitting models, as well as how to leverage tidymodels to do

more elaborate things like resampling and tuning hyperparameters. We’ll

fit a final model, then use that to predict subtypes of an entirely new

dataset.

This vignette tries to assume very little knowledge about machine

learning or tidymodels.

Fitting

A simple fit

Let’s start with the fitting procedure. We first need gene expression data.

The data I’m using is from Sjödahl et al. (2012). It contains RNA expression from 308 bladder cancer tumors.

lund <- s3readRDS("lund.rds", "reclanc-lund", region = "us-east-2")

lund

#> ExpressionSet (storageMode: lockedEnvironment)

#> assayData: 16940 features, 308 samples

#> element names: exprs

#> protocolData: none

#> phenoData

#> sampleNames: UC_0001_1 UC_0002_1 ... UC_0785_1 (308 total)

#> varLabels: title source ... sample (16 total)

#> varMetadata: labelDescription

#> featureData: none

#> experimentData: use 'experimentData(object)'

#> Annotation:In their paper, Sjödahl et al. used the transcriptional data to classify the tumors into seven molecular subtypes (MS):

table(lund$molecular_subtype)

#>

#> MS1a MS1b MS2a.1 MS2a.2 MS2b.1 MS2b2.1 MS2b2.2

#> 53 78 30 55 43 20 29We’d like to apply this subtype framework to other datasets. To do this, we first need to generate centroids. Before we can begin, though, we need to convert our outcomes to factors. In this case, our outcomes are the molecular subtypes:

lund$molecular_subtype <- factor(lund$molecular_subtype)In its simplest form, since clanc accepts

ExpressionSet objects, we could do the following and be

done with it:

simple_centroids <- clanc(lund, classes = "molecular_subtype", active = 5)

head(simple_centroids$centroids)

#> class gene expression pooled_sd active prior

#> 1 MS1a CXCL1 6.534490 0.8749133 5 0.1428571

#> 2 MS1a MMD 7.922508 0.6429620 5 0.1428571

#> 3 MS1a C9orf19 8.378910 0.7510552 5 0.1428571

#> 4 MS1a BNC1 5.297095 0.2106762 5 0.1428571

#> 5 MS1a SLFN11 7.362887 0.6824663 5 0.1428571

#> 6 MS1a CRAT 6.004517 0.3425669 5 0.1428571The problem with this method, though, is we have no idea if this is a

good fit or not. active is an argument that specifies the

number of genes that are used as distinguishing features for a given

class. In this case, each class will find 5 genes that have expression

patterns peculiar to that given molecular subtype, and each subtype will

have 7 (the total number of subtypes) x 5 (number of active genes) = 35

genes in it (see my blog post or -

better yet - the

original paper for more details). Could we have gotten a better fit

with more genes? Are we selecting more genes than we need? How would we

know?

Setting the stage for more elaborate analyses

Before we can get started on tackling these larger questions, let’s

take a brief detour to the land of tidymodels.

tidymodels is a collection of packages that make running

and tuning algorithms like this much less painful and much more

standardized.

In order to leverage tidymodels, we need to buy-in to

their data structures.

(Aside: I don’t mean to make the buy-in sound begrudging. When I say

need, I really mean it: we’re going to be specifying very long formulas,

which for some reason R really, really hates. Emil Hvitfeldt

recently (at time of writing) has allowed

tidymodels to handle long formulas gracefully, so using

tidymodels infrastructure is a gift, not a chore.)

Many tidymodels workflows begin with a model

specification. The rationale behind this is to separate the

model specification step from the model fitting step

(whereas in base R, they generally all happen at once).

reclanc makes it easy to specify a model by adding a custom

engine to parsnip::discrim_linear, so specifying a model

looks like this:

mod <- discrim_linear() |>

set_engine(

engine = "clanc", # Note: "clanc", not "reclanc"

active = 5

)This mod doesn’t do anything - and that’s kind of the

point: it only specifies the model we will later fit with, but doesn’t

do any fitting itself. This allows us to reuse the specification across

our code.

The next step is to wrangle our data a bit to be in a ‘wide’ format, where all columns are outcomes (classes) and predictors (genes), and all rows are observations (samples):

wrangled <- data.frame(class = lund$molecular_subtype, t(exprs(lund)))

head(wrangled[1:5])

#> class LOC23117 FCGR2B TRIM44 C15orf39

#> UC_0001_1 MS1b 5.565262 5.306654 9.305053 6.430063

#> UC_0002_1 MS2b.1 5.505854 5.731128 9.242790 7.265748

#> UC_0003_1 MS2a.2 5.336140 5.540470 9.888668 7.244976

#> UC_0006_2 MS2b.1 5.576748 5.847743 9.408895 7.377358

#> UC_0007_1 MS2a.2 5.414919 5.510507 10.482469 6.435552

#> UC_0008_1 MS2b.1 5.279174 5.633093 9.112754 7.057977Finally, we specify a formula for fitting the model. This uses the

recipes package from tidymodels. While this is

a delightful package that can help you preprocess your data, it’s out of

the scope of this vignette. Instead, just think of it as a way to

specify a formula that keeps R from blowing up:

# Note that the recipe requires 'template data'

recipe <- recipe(class ~ ., wrangled) We can bundle our model specification (mod) and our

preprocessing steps (recipe, which is just a formula) into

a workflow:

wf <- workflow() |>

add_recipe(recipe) |>

add_model(mod)

wf

#> ══ Workflow ════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

#> Preprocessor: Recipe

#> Model: discrim_linear()

#>

#> ── Preprocessor ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

#> 0 Recipe Steps

#>

#> ── Model ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

#> Linear Discriminant Model Specification (classification)

#>

#> Engine-Specific Arguments:

#> active = 5

#>

#> Computational engine: clancNow we can fit our model:

tidymodels_fit <- fit(wf, data = wrangled)

head(extract_fit_parsnip(tidymodels_fit)$fit$centroids)

#> class gene expression pooled_sd active prior

#> 1 MS1a CXCL1 6.534490 0.8749133 5 0.1428571

#> 2 MS1a MMD 7.922508 0.6429620 5 0.1428571

#> 3 MS1a C9orf19 8.378910 0.7510552 5 0.1428571

#> 4 MS1a BNC1 5.297095 0.2106762 5 0.1428571

#> 5 MS1a SLFN11 7.362887 0.6824663 5 0.1428571

#> 6 MS1a CRAT 6.004517 0.3425669 5 0.1428571You’ll notice that our results are the same as what we saw

previously, demonstrating that while we’re using tidymodels

rather than base R, we’re still doing the same thing.

Measuring fit accuracy with cross-validation

Now that we’ve dialed in to the tidymodels framework, we

can do a lot of elaborate things with ease. One of our concerns is

whether 5 active genes was a good choice (active = 5). A

somewhat simple way to determine how good our choice of 5 genes is to

use cross-validation.

Cross-validation allows us to test how good our fit is by training our

model on, say, 80% of our data, and testing it on the rest (see the

Wikipedia diagram of a k-fold cross validation). This allows us to get a

measure of how good our fit is, without having to break out our actual

test data - which in general should only be used when we’re ready to

finalize our model.

Speaking of test data, let’s go ahead and split that off now. We’ll lock our test data away and only use it once we’ve fit our final model. Until then, we’ll use cross validation to assess how good the fit is, essentially using our training data as its own testing data.

Of course, tidymodels makes this easy too, by using

rsample::initial_split:

set.seed(123)

splits <- initial_split(wrangled, prop = 0.8, strata = class)

train <- training(splits)

test <- testing(splits)train and test are just subsets of the

original data, containing 80% and 20% of the original data

(respectively). It also tries to maintain the relative proportions of

each of the classes within each of the datasets (because we set

strata = class):

round(prop.table(table(train$class)), 2)

#>

#> MS1a MS1b MS2a.1 MS2a.2 MS2b.1 MS2b2.1 MS2b2.2

#> 0.17 0.25 0.10 0.18 0.15 0.07 0.08

round(prop.table(table(test$class)), 2)

#>

#> MS1a MS1b MS2a.1 MS2a.2 MS2b.1 MS2b2.1 MS2b2.2

#> 0.19 0.27 0.08 0.16 0.11 0.05 0.16Creating folds for cross validation is nearly the same as

initial_split:

folds <- vfold_cv(train, v = 5, strata = class)

folds

#> # 5-fold cross-validation using stratification

#> # A tibble: 5 × 2

#> splits id

#> <list> <chr>

#> 1 <split [193/51]> Fold1

#> 2 <split [193/51]> Fold2

#> 3 <split [195/49]> Fold3

#> 4 <split [197/47]> Fold4

#> 5 <split [198/46]> Fold5We can reuse our workflow wf, which contains our model

and formula. The only difference is that we use

fit_resamples, and we specify a metric we want to use to

measure how good our fit is (remember that every fold has a chunk of

data it uses to test the fit). For simplicity, let’s use accuracy:

fits <- fit_resamples(

wf,

folds,

metrics = metric_set(accuracy)

)

#> 35/35 (100%) genes in centroids found in data

#> 35/35 (100%) genes in centroids found in data

#> 35/35 (100%) genes in centroids found in data

#> 35/35 (100%) genes in centroids found in data

#> 35/35 (100%) genes in centroids found in data

fits

#> # Resampling results

#> # 5-fold cross-validation using stratification

#> # A tibble: 5 × 4

#> splits id .metrics .notes

#> <list> <chr> <list> <list>

#> 1 <split [193/51]> Fold1 <tibble [1 × 4]> <tibble [0 × 3]>

#> 2 <split [193/51]> Fold2 <tibble [1 × 4]> <tibble [0 × 3]>

#> 3 <split [195/49]> Fold3 <tibble [1 × 4]> <tibble [0 × 3]>

#> 4 <split [197/47]> Fold4 <tibble [1 × 4]> <tibble [0 × 3]>

#> 5 <split [198/46]> Fold5 <tibble [1 × 4]> <tibble [0 × 3]>We can then extract our accuracy metrics by using

collect_metrics, which roots around in each of our fits and

helpfully extracts the metrics, aggregates them, and calculated the

standard error:

metrics <- collect_metrics(fits)

metrics

#> # A tibble: 1 × 6

#> .metric .estimator mean n std_err .config

#> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <chr>

#> 1 accuracy multiclass 0.737 5 0.0289 Preprocessor1_Model1Our model has an accuracy of about 74%. Applying this model to our testing data:

# Fit a model using *all* of our training data

final_fit <- clanc(class ~ ., train, active = 5)

# Use it to predict the (known) classes of our test data

preds <- predict(final_fit, new_data = test, type = "class")

#> 35/35 (100%) genes in centroids found in data

w_preds <- cbind(preds, test)

# Compare known class vs predicted class

metric <- accuracy(w_preds, class, .pred_class)

metric

#> # A tibble: 1 × 3

#> .metric .estimator .estimate

#> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

#> 1 accuracy multiclass 0.734Note that our testing data accuracy (%) approximates the training data accuracy (74%).

Tuning hyperparameters with tune

Now we at least have some measure of how good our model

fits, but could it be better with more genes? Could we get away with

fewer? Running the same command over and over again with different

numbers is a drag - fortunately, there’s yet another beautiful package

to help us: tune.

To use tune, we need to re-specify our model to let

tune know what parameters we want to tune:

tune_mod <- discrim_linear() |>

set_engine(

engine = "clanc",

active = tune()

)We could update our previous workflow using

update_model, but let’s just declare a new one:

tune_wf <- workflow() |>

add_recipe(recipe) |>

add_model(tune_mod)We then have to specify a range of values of active to

try:

values <- data.frame(active = seq(from = 1, to = 50, by = 4))

values

#> active

#> 1 1

#> 2 5

#> 3 9

#> 4 13

#> 5 17

#> 6 21

#> 7 25

#> 8 29

#> 9 33

#> 10 37

#> 11 41

#> 12 45

#> 13 49We can then fit our folds using the spread of values we

chose:

# This is going to take some time, since we're fitting 5 folds 13 times each.

tuned <- tune_grid(

tune_wf,

folds,

metrics = metric_set(accuracy),

grid = values

)

tuned

#> # Tuning results

#> # 5-fold cross-validation using stratification

#> # A tibble: 5 × 4

#> splits id .metrics .notes

#> <list> <chr> <list> <list>

#> 1 <split [193/51]> Fold1 <tibble [13 × 5]> <tibble [0 × 3]>

#> 2 <split [193/51]> Fold2 <tibble [13 × 5]> <tibble [0 × 3]>

#> 3 <split [195/49]> Fold3 <tibble [13 × 5]> <tibble [0 × 3]>

#> 4 <split [197/47]> Fold4 <tibble [13 × 5]> <tibble [0 × 3]>

#> 5 <split [198/46]> Fold5 <tibble [13 × 5]> <tibble [0 × 3]>As before, we can collect our metrics - this time, however, we have a

summary of metrics for each of values for active:

tuned_metrics <- collect_metrics(tuned)

tuned_metrics

#> # A tibble: 13 × 7

#> active .metric .estimator mean n std_err .config

#> <dbl> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <chr>

#> 1 1 accuracy multiclass 0.585 5 0.0368 Preprocessor1_Model01

#> 2 5 accuracy multiclass 0.737 5 0.0289 Preprocessor1_Model02

#> 3 9 accuracy multiclass 0.748 5 0.0496 Preprocessor1_Model03

#> 4 13 accuracy multiclass 0.781 5 0.0403 Preprocessor1_Model04

#> 5 17 accuracy multiclass 0.770 5 0.0280 Preprocessor1_Model05

#> 6 21 accuracy multiclass 0.774 5 0.0335 Preprocessor1_Model06

#> 7 25 accuracy multiclass 0.785 5 0.0378 Preprocessor1_Model07

#> 8 29 accuracy multiclass 0.794 5 0.0319 Preprocessor1_Model08

#> 9 33 accuracy multiclass 0.773 5 0.0281 Preprocessor1_Model09

#> 10 37 accuracy multiclass 0.790 5 0.0295 Preprocessor1_Model10

#> 11 41 accuracy multiclass 0.794 5 0.0339 Preprocessor1_Model11

#> 12 45 accuracy multiclass 0.815 5 0.0267 Preprocessor1_Model12

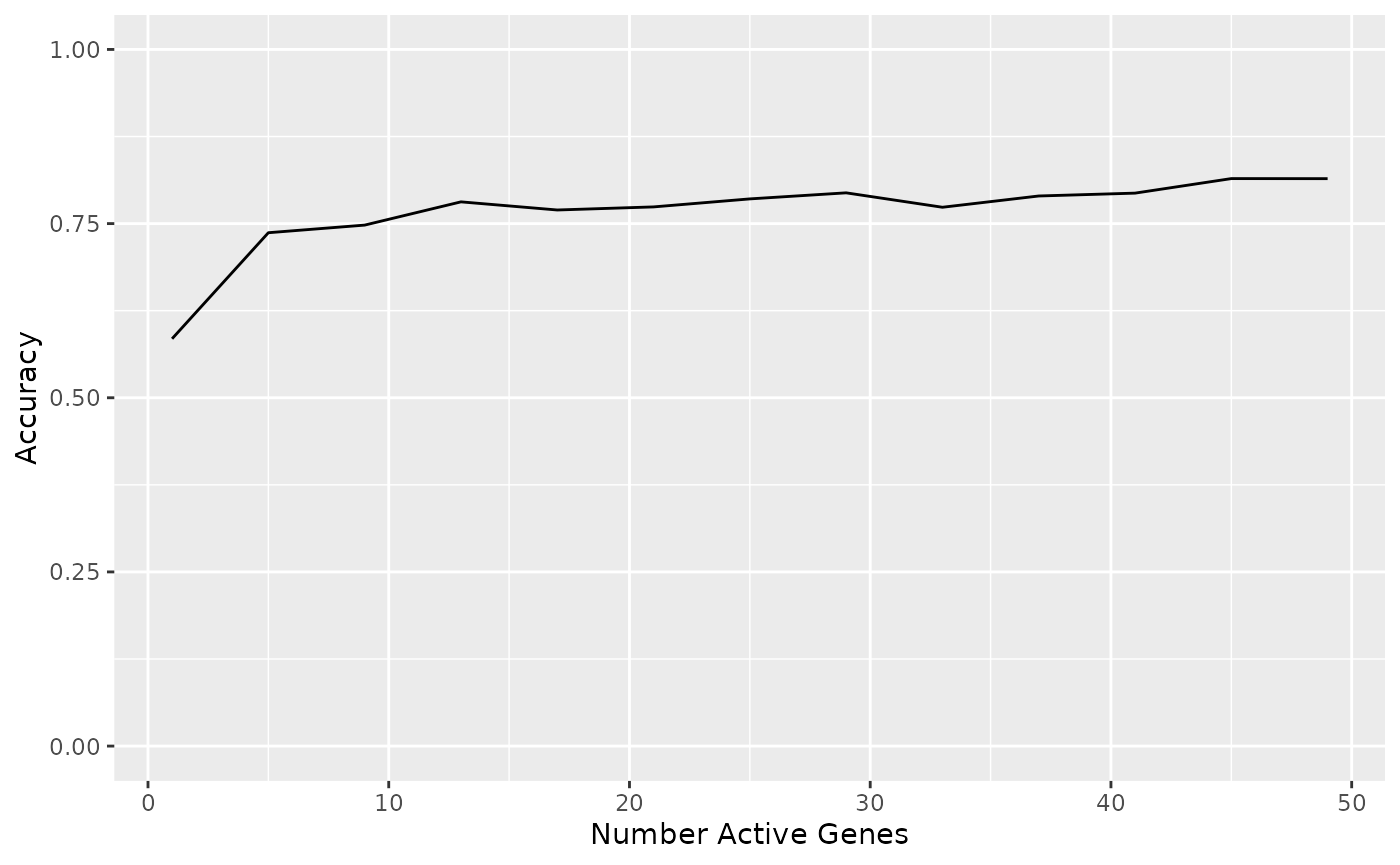

#> 13 49 accuracy multiclass 0.815 5 0.0277 Preprocessor1_Model13Or graphically:

ggplot(tuned_metrics, aes(active, mean)) +

geom_line() +

coord_cartesian(ylim = c(0, 1)) +

labs(x = "Number Active Genes", y = "Accuracy")

It looks like we read maximal accuracy at around 21 genes - let’s choose 20 genes for a nice round number:

final_fit_tuned <- clanc(class ~ ., data = train, active = 20)

# Use it to predict the (known) classes of our test data:

preds <- predict(final_fit_tuned, new_data = test, type = "class")

#> 140/140 (100%) genes in centroids found in data

w_preds <- cbind(preds, test)

# Compare known class vs predicted class:

metric <- accuracy(w_preds, class, .pred_class)

metric

#> # A tibble: 1 × 3

#> .metric .estimator .estimate

#> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

#> 1 accuracy multiclass 0.812It looks like our accuracy is a little better now that we’ve chosen an optimal number of active genes.

Predicting

Now we want to apply our classifier to new data. Our second dataset is RNAseq data from 30 bladder cancer cell lines:

library(cellebrate)

cell_rna

#> class: DESeqDataSet

#> dim: 18548 30

#> metadata(1): version

#> assays(2): counts rlog_norm_counts

#> rownames(18548): TSPAN6 TNMD ... MT-ND5 MT-ND6

#> rowData names(0):

#> colnames(30): 1A6 253JP ... UC7 UC9

#> colData names(5): cell bsl lum call cladePredicting is incredibly simple. Since we’re using a different

sequencing method (RNAseq vs array-based sequencing), it probably makes

sense to use a correlation based classification rather than the original

distance-based metric used in the original ClaNC package. We can do that

by specifying type = "numeric" and then whatever

correlation method we prefer.

cell_preds <- predict(

final_fit_tuned,

cell_rna,

assay = 2,

type = "numeric",

method = "spearman"

)

#> 118/140 (84%) genes in centroids found in data

out <- cbind(colData(cell_rna), cell_preds) |>

as_tibble()

out

#> # A tibble: 30 × 12

#> cell bsl lum call clade .pred_MS1a .pred_MS1b .pred_MS2a.1

#> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 1A6 99.0 1.02 BSL Epithelial Other 0.0600 0.224 0.149

#> 2 253JP 76.6 23.4 BSL Unknown 0.0574 0.240 0.219

#> 3 5637 98.5 1.46 BSL Epithelial Other 0.0958 0.243 0.160

#> 4 BV 49.9 50.1 LUM Unknown 0.0758 0.262 0.238

#> 5 HT1197 56.0 44.0 BSL Epithelial Other 0.119 0.288 0.224

#> 6 HT1376 10.9 89.1 LUM Epithelial Other 0.100 0.277 0.238

#> 7 J82 98.1 1.91 BSL Mesenchymal 0.127 0.292 0.219

#> 8 RT112 0 100 LUM Luminal Papilla… 0.173 0.380 0.294

#> 9 RT4 0 100 LUM Luminal Papilla… 0.134 0.317 0.257

#> 10 RT4V6 0 100 LUM Luminal Papilla… 0.143 0.207 0.165

#> # ℹ 20 more rows

#> # ℹ 4 more variables: .pred_MS2a.2 <dbl>, .pred_MS2b.1 <dbl>,

#> # .pred_MS2b2.1 <dbl>, .pred_MS2b2.2 <dbl>

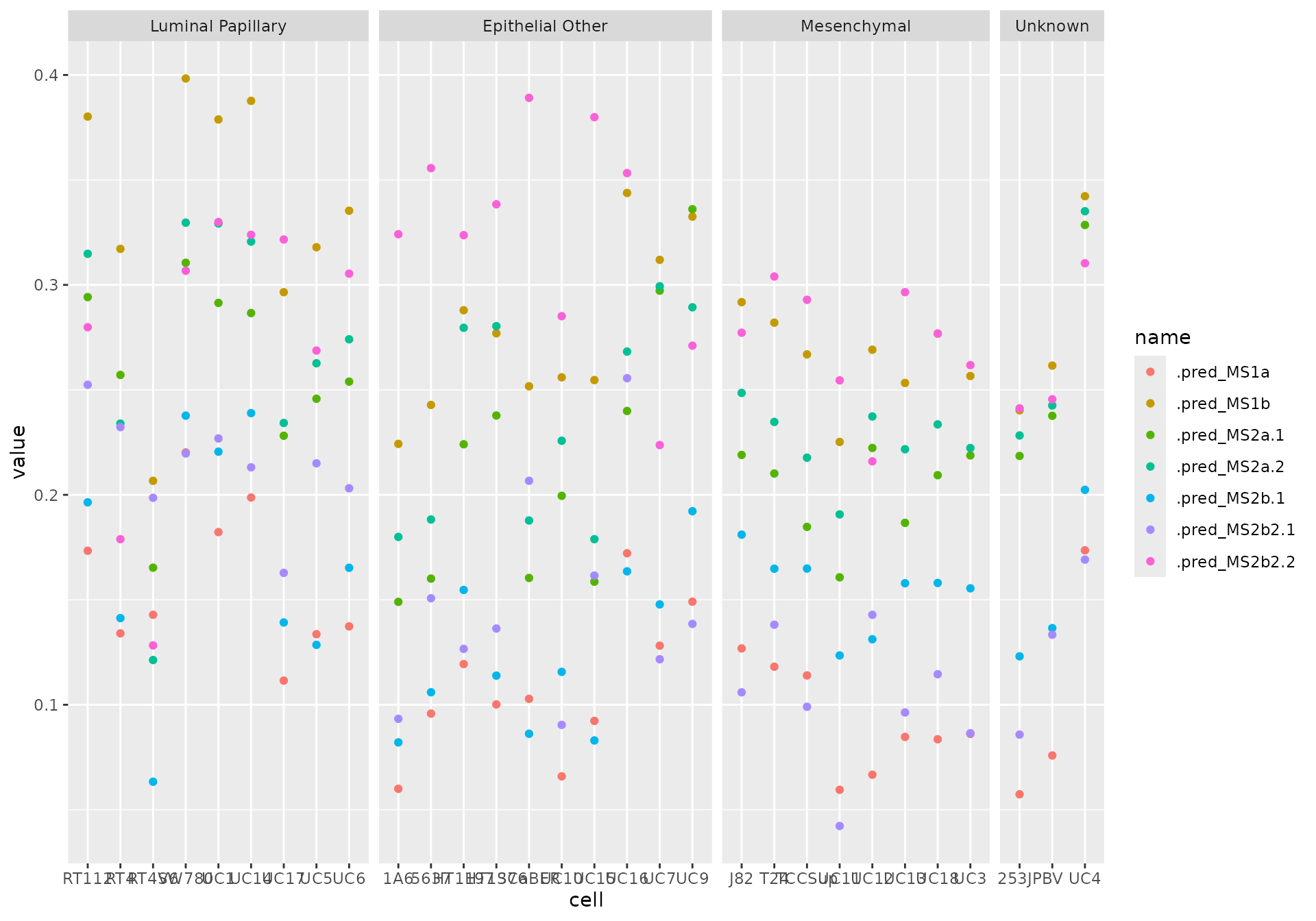

plotting_data <- out |>

pivot_longer(cols = starts_with(".pred"))

plotting_data |>

ggplot(aes(cell, value, color = name)) +

geom_point() +

facet_grid(~clade, scales = "free_x", space = "free_x")

In the Sjödahl paper, the seven subtypes were simplified into five subtypes by merging some of the two that had similar biological pathways activated. To ease interpretation, we can do that too:

table <- plotting_data |>

summarize(winner = name[which.max(value)], .by = c(cell, clade)) |>

mutate(

five = case_when(

winner %in% c(".pred_MS1a", ".pred_MS1b") ~ "Urobasal A",

winner %in% c(".pred_MS2a.1", ".pred_MS2a.2") ~ "Genomically unstable",

winner == ".pred_MS2b.1" ~ "Infiltrated",

winner == ".pred_MS2b2.1" ~ "Uro-B",

winner == ".pred_MS2b2.2" ~ "SCC-like"

)

) |>

relocate(cell, five, clade)

print(table, n = 30)

#> # A tibble: 30 × 4

#> cell five clade winner

#> <chr> <chr> <fct> <chr>

#> 1 1A6 SCC-like Epithelial Other .pred_MS2b2.2

#> 2 253JP SCC-like Unknown .pred_MS2b2.2

#> 3 5637 SCC-like Epithelial Other .pred_MS2b2.2

#> 4 BV Urobasal A Unknown .pred_MS1b

#> 5 HT1197 SCC-like Epithelial Other .pred_MS2b2.2

#> 6 HT1376 SCC-like Epithelial Other .pred_MS2b2.2

#> 7 J82 Urobasal A Mesenchymal .pred_MS1b

#> 8 RT112 Urobasal A Luminal Papillary .pred_MS1b

#> 9 RT4 Urobasal A Luminal Papillary .pred_MS1b

#> 10 RT4V6 Urobasal A Luminal Papillary .pred_MS1b

#> 11 SCaBER SCC-like Epithelial Other .pred_MS2b2.2

#> 12 SW780 Urobasal A Luminal Papillary .pred_MS1b

#> 13 T24 SCC-like Mesenchymal .pred_MS2b2.2

#> 14 TCCSup SCC-like Mesenchymal .pred_MS2b2.2

#> 15 UC10 SCC-like Epithelial Other .pred_MS2b2.2

#> 16 UC11 SCC-like Mesenchymal .pred_MS2b2.2

#> 17 UC12 Urobasal A Mesenchymal .pred_MS1b

#> 18 UC13 SCC-like Mesenchymal .pred_MS2b2.2

#> 19 UC14 Urobasal A Luminal Papillary .pred_MS1b

#> 20 UC15 SCC-like Epithelial Other .pred_MS2b2.2

#> 21 UC16 SCC-like Epithelial Other .pred_MS2b2.2

#> 22 UC17 SCC-like Luminal Papillary .pred_MS2b2.2

#> 23 UC18 SCC-like Mesenchymal .pred_MS2b2.2

#> 24 UC1 Urobasal A Luminal Papillary .pred_MS1b

#> 25 UC3 SCC-like Mesenchymal .pred_MS2b2.2

#> 26 UC4 Urobasal A Unknown .pred_MS1b

#> 27 UC5 Urobasal A Luminal Papillary .pred_MS1b

#> 28 UC6 Urobasal A Luminal Papillary .pred_MS1b

#> 29 UC7 Urobasal A Epithelial Other .pred_MS1b

#> 30 UC9 Genomically unstable Epithelial Other .pred_MS2a.1